The Spices Research Station

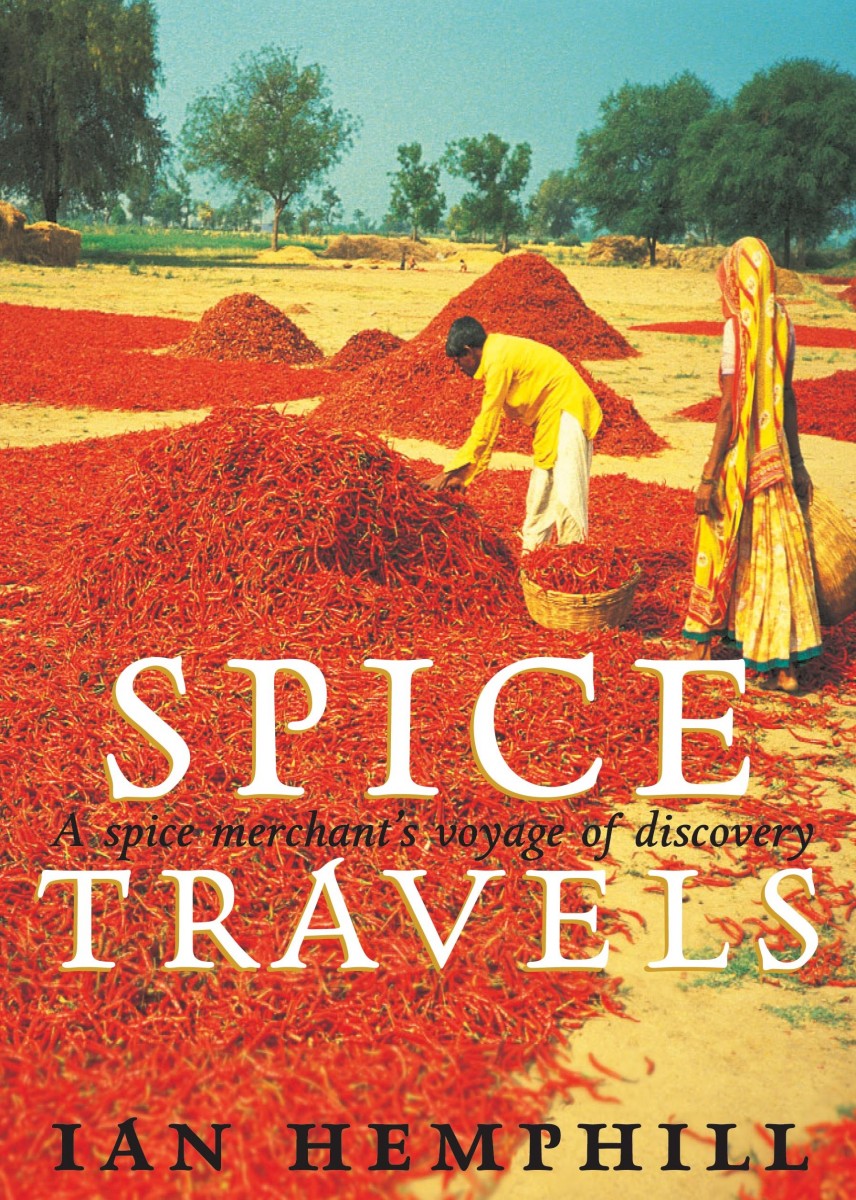

Where else in the world but India would you find a Spices Research Station? Fortunately for those of us who are consumed by the lifelong passion for all things associated with spices, India takes this subject very seriously. In fact more so than any other country in the world. Therefore when we took our Spice Discovery Tour to India in March 1991, it would not have been complete without a visit to the Spices Research Station in Gujerat in the north-western state of Ahmedabad. Our objective was to see where agricultural research is undertaken for India’s seed spices. Spices come from many different parts of plants, but the group that makes the greatest varietal contribution is the aromatic seeds of a wide range of annual plants. While spices gathered from the roots, fruits, berries, bark and buds of plants, shrubs and trees, tend to come from the tropical zones north and south of the equator, seed spices are mostly grown in the temperate zones further north and south. Although trade over many centuries has made most spices readily available in even remote areas, one will notice in regional cuisines a tendency to favour those spices that are most readily available. So in the south of India, pepper, cardamom, ginger and turmeric will dominate, while in the north we see frequent use of fenugreek, cumin, dill, ajowan, fennel, mustard and coriander seeds.

The flight to Ahmedabad had taken us via a short stopover in Bombay (now referred to as Mumbai). The drive from the airport to the hotel in Mumbai provided more culture shocks for our group of intrepid travellers. Our rattly old bus crawled through almost stationary traffic, while the most incredible crush of humanity was fascinating, exciting and disturbing. We passed families who lived permanently on the footpaths surrounded by their meagre possessions, (one even with a chook), or they dwelt in humpeys made of hessian bags. Cows with arched horns, their pointed tips painted blue, wandered amongst the throng, seemingly oblivious to the honking horns, trucks, bicycles and urchins weaving around them. A rustic, hand-pulled cart with the body of an old man on it trundled by the bus window. Some of us could not avert our eyes from this sight, unfamiliar, irreverent and uncivilised by our standards. Others looked away out of respect for the departed. You see things here you wish you hadn’t, remember them later and are grateful you have. This is India, emotion, contradiction, fascination, voyeurism, cynicism, beauty and pragmatism, all assaulting the senses at once. Arriving at the majestic Taj Mahal hotel, overlooking India Gate, provided a cool, comfortable haven from the heat and intensity of so much humanity outside.

Although appreciating this unrealistic haven like a pair of 18th Century Victorian ninnies, we felt ashamed at our cowardice by indulging in such comfort while there was so much out there to see. So we ventured forth early the next morning as the crowds stirred and the nearby markets were beginning to open. We strolled through street markets, goodness knows when the streets ever get used to convey traffic, crammed with stalls selling a wonderful variety of good quality fresh fruits and vegetables. We couldn’t help noticing how many vegetables look smaller than our highly fertilised, irrigated produce back home, however when tasted, these humble offerings in bright, natural ripeness convey a richness of flavour that reminds me of dad’s home-grown vegetables. There were little tomatoes, not the trendy cherry tomatoes we know, that would be shunned in our supermarkets from lack of size. One of these morsels seemed to have as much flavour in its compact sphere as two mass-produced tomatoes of double the size.

We passed a barrow the size of a small utility truck, piled high with tiny, virgin-white, potent garlic bulbs (Allium sativum). Besides their size, these little bulbs looked much like the garlic we are used to seeing. Each bulb is a round, lumpy collection of bulblets encased in parchment-like, flaky, outer-skin, resembling tightly clenched knuckles wrapped in tissue paper. These bulblets are commonly called ‘cloves’, a term often found in recipe books and bearing no relationship whatsoever to the spice we call cloves. Liz spotted a large brass bucket that we couldn’t resist buying for about A$15. We continued to fill it with purchases, gee gaws and bric-a-brac for our little girls, and by some traveller’s quirk, somehow convinced the airline to allow us to bring it home as cabin luggage. The fish markets, which we usually avoid, were clean. Thankfully, at the cool beginning of the day they had not yet developed their characteristic pong. Fish of all sizes were on sale, neatly laid out by merchants sitting cross-legged behind their silvery displays of no more than thirty gutted offerings. A buyer haggles with the merchant, who with fish scale encrusted, calloused hands turns the shiny carcass to glisten and reveal its fresh appearance, while convincing his customer what good value it is. We hurried past the cleaning area, entrails slithering between deft, knife wielding workers feet as they fell, squishy on the concrete floor, before being shoveled away.

By now my head was starting to spin from environment input overload. So much that was so foreign yet so exciting was going on all around us, yet it was becoming difficult to absorb it all. We took respite at a small ‘hotel’, hotels in the streets here being more like a café than a hostelry. Weak black tea lightly spiced with cardamom refreshed us while we spread out our purchases for the girls. Bangles, rings, hair-clips and sunglasses will make a good number of little parcels to hand out as our three daughters bounce excitedly around us when we get home and unpack our bags.

As we flew to Ahmedabad in the northwest of India, we recalled our experiences in Hyderabad to the east, and wondered how would they be different. By contrast, Hyderabad we knew to be relatively wealthy, something confirmed upon our arrival there. The Hyderabad Oberoi struck us as something between the Shan-gri-la of Lost Horizon and Nirvana. We were greeted there by acres of marbled high ceilings, solid carved wood doors, highly polished marble in the bathrooms, expansive open areas, a swimming pool and panoramic views. Our guide in Hyderabad, Satish, had not experienced a group that wanted to go bush rather than linger over local sights including the magnificent Golconda Fort. However he had done his homework and we headed off out of town with a picnic lunch packed by the hotel. The bus lurched to a halt in front of a Muslim arms shop, and as Satish alighted we joked about whether he was collecting an issue of weapons for our protection. Nothing so dramatic, he emerged with two enormous red rugs for us to sit on later when we had our picnic lunch.

As we got further out of Hyderabad the traffic thinned, horns blared less frequently and the density of population became less. Our first stop was at a jasmine garden where marigolds, roses and chrysanthemums were also growing. The jasmine was tied up like a bush, so the flowers would form prolifically on the outside for easy access when picking. Flowers are an important element in Indian life, whether it is for devotional purposes, the way married Hindu women wear flowers in their hair every day, or for sheer pleasure, blossoms are on sale every day in every market. The aroma of picked flowers was intoxicating as their fragrances leeched into the warming morning air and evoked a deep childhood memory. It was in the mid nineteen sixties when my father made pot-pourri from rose petals, various scented-leaved geraniums, lavender and calendula flowers, lemon verbena, cinnamon, cloves, orris root powder and essential oils. I remember the family picking these fragrant ingredients on balmy, bee-laden days. Dad then dried the harvest and brought it together to make pot-pourri in a veritable act of alchemy. When I experience the fragrance of flowers, it does sadden me to see how the notion of a pot-pourri has become debased. These days, it is either just another commercial room-freshener, redolent with sickly, artificial scents, or an extremely poor imitation of the original concept, but made of poor quality dried leaves and coloured wood shavings. I emerged from my reverie as we watched some women nimbly gathering the delicate blooms, and carrying large baskets containing their harvest on their heads, with long-necked, straight-backed gliding elegance.

The next village we drove through was where Satish had grown up, its streets barely wide enough to accommodate the bus. One could have reached out the windows and touched the shops and stalls as we drove past them. Every aspect of village life was carrying on around us, merchants selling their wares, tailors sewing, men lazily drinking coffee and smoking or urinating against walls, children scampering around like little jackrabbits. We strained up a steep rise, the bus chugging around a sharp bend in the road and then it stopped at a pillbox that looked like the local police post. Satish got out and for about five minutes was engaged in heated conversation with the uniformed, mustached, baton-under-the-arm policeman. Some money changed hands, Satish climbed back on board and we were on our way again.

The road began to get bumpier and occasionally we heard some alarming knocks and clunks in the bus’s suspension and imagined what it would be like to have a broken spring, axle or tail shaft out here. Our attention was soon drawn from the prospect of mechanical breakdown when we came upon some enormous brick structures that were traditional brickworks. Like so many experiences in this country, we could have been in a time-warp from centuries ago. The people working here were not locals, but comprised about twenty families from Orissa. Amongst the workers were about ten Gypsies wearing an abundance of ornate silver bands on their arms and legs, and brightly coloured clothes. More silver ornaments were braided into their hair, setting off bright smiles and a decidedly cheeky demeanor. These women were warm and friendly and not one hand shot out in begging mode. Instead they spontaneously formed a circle around us and did a beautiful rhythmic dance accompanied by singing. The other workers gathered around to watch until the boss came over and scolded them all back to work. How lucky we were to experience something so warm and uncontrived, the Gypsies sharing some of their culture for the simple joy of it. Satish told us these workers need to make about 750 bricks to make jus one dollar, hard work indeed, especially when one sees a little woman carrying ten bricks on her head as the kiln is loaded. These kilns have been made in a similar fashion for centuries. Basically a huge monolith of bricks is stacked up to ten metres high, fifty metres long and twenty metres wide. A firebox in the middle, aspirated by vents left open during the construction, burns for weeks inside until the whole structure is baked and ready to be dismantled and the bricks sold.

The road deteriorated greatly as the bus was able to average no more than ten kilometres per hour until we arrived at the small village of Kodlapadkal, a remote settlement where we were told no other tourists had been before. The only white people seen there in the last ten years were some research workers with the United Nations. All the houses were made of mud with thatched roofs and everything was incredibly neat and clean. The dirt alleys were swept and there was no refuse lying around like you see in the cities. As we have experienced with most country folk, these people were warm and friendly and as curious to see us as we were to see them. We were all acutely aware of the importance of not behaving in a manner that would disturb their way of life, which appeared to us nothing short of idyllic. We observed them going about their daily chores, making pots, weaving matting, children playing, old people chatting. The villagers entertained us and we them for an hour and a half until we farewelled them. Everyone was quite quiet on the bus, just cherishing our experience and hoping that as civilization encroaches upon this remote area, the inhabitants benefit from the good aspects of progress and are not demeaned by the greedy, bad and ugly.

The bus pulled up beside a huge tamarind tree (Tamarindus indica) and Satish and the driver laid out the enormous red rugs on the ground under the shade of its spreading branches. There is a belief that tamarind trees emit harmful, acrid vapours, making it unsafe to sleep under them and that plants will not grow there due to the acidity exhaled from the tree overnight. This may be why there is usually little vegetation around their bases, creating an ideal picnic spot in the middle of a hot Indian March day. Tamarind trees bear 10cm long fruits that are knobbly, light-brown pods containing an acidic pulp that surrounds about 10 shiny, smooth, dark brown, angular seeds, measuring roughly 4mm x 10mm. The bulbous, knuckle-like pod has a brittle shell, which when broken away reveals a pale-tan, sticky mass with longitudinal strings and fibrous veins attached. Upon coming into contact with the air, the pulp begins to oxidise and turns dark brown and almost black. Its aroma is vaguely fruity and sharp while the flavour is intensely acidic, tingling, refreshing and reminiscent of dried stone fruit. Tamarind is arguably the most popular souring agent in Indian cooking after lime or lemon. I like to make a refreshing soft drink by adding soda water and ice cubes to a tablespoon of tamarind water with a little sugar.

The hour or so spent over the very un-Indian hotel packed lunch of sandwiches, fresh fruit and hard-boiled eggs, passed with relaxed conversation and some hilarity under our tamarind tree. We wanted to thank the villagers of Kodlakalpal for their hospitality, so after consultation with Satish, we passed the hat around and made a donation to a fund that had been established to install a pump for their well.

With memories of a far off primitive village already beginning to fade from the onslaught of new experiences, our flight touched-down in Ahmedabad, northwest of Bombay and the closest we came to the Pakistan border.

At this time of year (March) before the monsoon, Ahmedabad was a dustbowl with so much air pollution that we kept the windows of the bus closed in spite of the heat. In stark contrast to our earlier sub-tropical adventures, we were surrounded by a dry, undulating landscape, reminiscent of Australia’s wheat belt. Just perfect conditions for seed crops. I can never doze on a bus because if I do I might miss something, such as a cart piled precariously high with a dry, mobile haystack of mustard straw and pulled by an equally straw-coloured haughty-looking camel. A group of women in bright saris, like bougainvillea flowers against the colourless background, working on road repairs. As the bus flashed past I caught glimpses of deep, beautiful eyes, their languid pupils suspended in bright contrasting whites. We received glistening broad smiles in dusky upturned faces as they paused from work and looked up at our out-of-place, peering-from-bus-window group hurtling by. The roads were as congested as any we had seen. The bus would frantically toot and weave its way through a tangle of pushcarts, camel and oxen drawn drays and light three-wheeler ‘auto rickshaws’ piled high with goods. Every now and then we’d inch past lumbering, suspension-challenged ‘Tata’ trucks that look just like 1950’s Mercedes trucks but bearing a large “T” on the bonnet instead of a three-pointed star. Another result of India cleverly buying outdated tooling to establish manufacturing as they did with the Morris Oxford, turning it into their Ambassador car.

Something a group of tourists has to come to terms with in India is that every city does not have a five-star hotel. When we arrived at the hotel Cama, reputed to be the best hotel in town, we saw a few jaws drop. It was characterised by flaking paint, mould marks on the walls, uneven floors, doors and door jambs that had seen far better days and a general atmosphere of resignation as to how wear and tear, the harsh summers and prolonged monsoons, all take their toll on a building. The beds were chiropractically firm, yet it was pleasing to discover how impeccably clean the bathrooms were. What endeared us most to the management at the Cama was their hospitality and efforts to make us comfortable. The chef had researched where we had come from and knowing that Australia had been a colony of England, went to great lengths to provide a meal of fish and chips followed by boiled pudding and custard. We appreciated their kindness but wished they’d served the food they are comfortable with preparing every day. Although the fish and chips left a lot to be desired (the cooking oil that is just perfect for Indian cooking is probably not the most appropriate medium to cook fish and chips in) the boiled pudding was fabulous. The next day we were treated to steak and mushroom pie followed by trifle (non-alcoholic). The other aspect our group of cheerful travellers had to come to terms with was that Gujerat is a ‘dry’ state. India has a number of states where alcohol is not allowed and we gathered from what we were told, that this occurs when a state is governed by Moslems. That means no alcohol is for sale or available in the hotel. No doubt our brain cells appreciated a few days respite from us slaking our thirsts with large amber bottles of cold Kingfisher beer in the less restrictive states.

We had made sure everyone was comfortable for the night, arranged wake-up calls for the morning and discussed the next day’s itinerary with Dr. Metha from the agricultural university at Jagadon, and a specialist in spices. No sooner were we asleep than, close to midnight, we heard the most incredible commotion in the street outside. Guns were going off, shouting and screams were punctuating the air and the percussion of sticks on tin reverberated through our flaking walls. Now the Gulf War was not long past and the underlying general feeling of anxiety while travelling was probably a bit more heightened than usual. “Bloody hell” I said to Liz as I shot bolt upright in bed with a start. “What on earth’s going on, has world war three started, what about our group, shit!” We sprang out of bed, tentatively pulling the curtains aside, peering out so as not to be seen by the rioting mob and surveyed what we expected to be a scene of bloody devastation. Instead, in the street below we saw a group of about fifty revelers, including a bevy of beautiful young women in red and gold saris. The cause of so much hubub in the dead of night we were informed matter-of-factly the next day, was a wedding procession.

Dr. Mehta met us early next morning to travel to the Spices Research Station and hopefully we would have time to see the spice market town of Unja in the afternoon. Dr. Mehta was a neat, short man with a pencil-thin moustache on the lower part of his top lip. He wore thick-lensed, black-framed spectacles, navy trousers and leather sandals. Like so many Indians in this hot and dusty environment, his spotlessly white shirt was impeccable and freshly ironed. Dr. Mehta had recently hosted an Australian from The South Australian Seed Grower’s Co-operative (SEEDCO) a few days earlier, and having developed somewhat of a rapport with one of our countrymen, felt very much at ease with our group. The visitor from SEEDCO was on a study mission because South Australia had developed a substantial coriander seed growing industry in its wheat producing areas and was keen to exchange information with the Indians. Instead of harvesting by hand, Australia’s coriander seed crop is harvested with wheat headers, making production in a country with high labour costs economically viable. Unfortunately for the visitor from South Australia, he had been a little too adventurous with his choice of eating establishments, and had succumbed to a major dose of ‘Delhi belly’ that culminated in him cutting short his stay. We prayed no such fate would befall us.

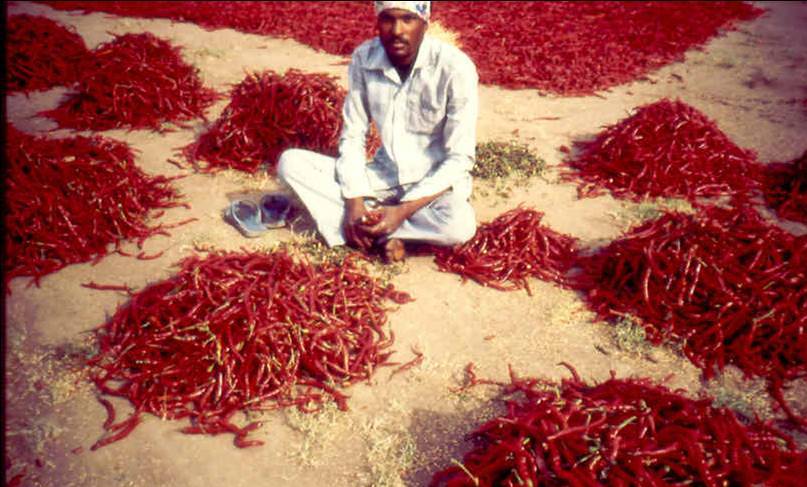

As we approached the Spices Research Station the earthy, familiar spicy aroma of cumin, tinged with the smell of wood-smoke from cooking fires, was in the air. Our first encounter upon arrival was a display of spices with statistics that I lapped up, while our group politely showed interest that was genuine but did not quite match my own. Seed spices represent about ten percent of India’s export of spices, which by 1991 was approaching 90,000 tonnes. Dr. Mehta explained how their research focused on three main areas, crop improvement, agronomics and plant protection.

Crop improvement came first, because as any farmer knows the search for varieties that are robust, high yielding and practical to harvest is a never-ending one. Agronomics relates to planting methods, timing and general plant husbandry, which will lead to high productivity. All of this work can be rendered useless, if the crops are then attacked by pests or diseases. Plant protection therefore is another essential aspect in their research, which we were impressed to learn included organic farming methods. The notion of organic farming (an oversimplification being farming without chemicals) had begun to gain some attention in India over recent years. This was because some exporters had experienced rejection of their shipments due to chemical residues. What really got up the Indian’s noses was the fact that the countries rejecting their produce were the very same nations that had been selling chemicals to the Indians in the first place.

Those of us in Western countries have an annoying habit of imposing stricter standards on developing countries as we become more financially secure than they are. We can afford the luxury of picking and choosing just what we believe is ‘morally’ right and will best suit our sensitive systems. Modern technology has also made it possible to measure residues in ‘parts per billion’ as opposed to the older ‘parts per million’, creating an awareness of residues we never even thought of in the past. I have no problem with us continuing to strive to improve standards in the interest of public health and wellbeing. I do have a problem however when we sanctimoniously chastise producers and block their sources of income without providing practical advice on alternatives. As it turns out, the Spices Board has made considerable progress with organic farming methods. Although only a handful of producers are certified organic, it appears that this method of farming may be one of the most practical ways to prevent crop rejection by overseas buyers.

post

post